John Henry Newman and Classical Education

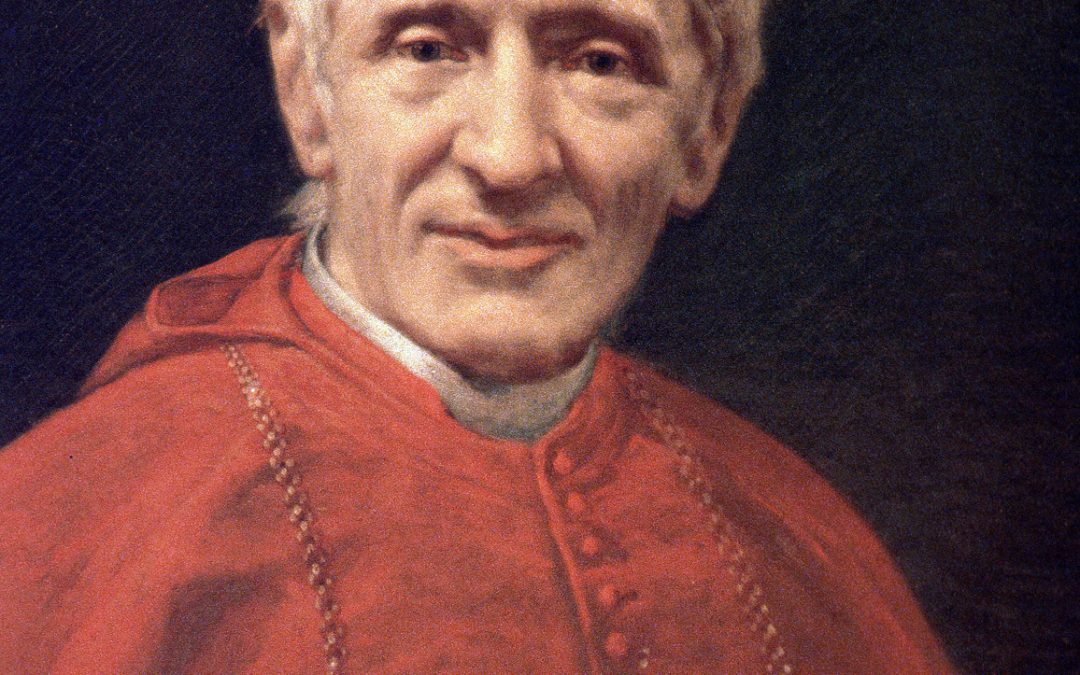

Some of you have heard of John Henry Newman, or Cardinal Newman as he is often called. Those of you seeking to renew the classical tradition of education, no doubt have come across Newman’s name, and some of you have read through at least parts of his famous book, The Idea of a University. This is a book and writer that cannot be ignored.

To understand the state of classical education in the Victorian era, when classical education was beginning to falter and diminish, Newman must be read. He is a bright light seeking to illuminate and preserve the classical tradition of education at a time when a great fog was rolling in, a time when a secular paradigm for learning was ascendant, a time when the value of studying classical languages, literature, and theology was being questioned and mocked. Newman held forth the flame, and not only defended the tradition, but managed to brilliantly restate it for his own time, and extend it.

Newman was born in 1801 in London. He went to Oxford University at the age of 16, and after graduating become a tutor at one of the colleges there—Oriel College. While serving as a tutor (professor) he also was ordained as a priest in the Church of England and served as the vicar St. Mary’s, the university church.

He and several other colleagues at Oxford become concerned with the ways they perceived the Anglican church to be drifting from its more liturgical and sacramental aspects and began to call for a return to traditional liturgies and practices that resembled those of the Roman Catholic Church. This renewal movement became known as the Oxford Movement and was described as Anglo-Catholic. Newman was the chief writer of many small pamphlets or tracts arguing for this “high church” renewal. In 1845, Newman was received into the Roman Catholic Church, and in 1879 was appointed a cardinal in the church–at the age of 78.

When Newman was asked to found a new Catholic University in Ireland, he delivered a series of nine lectures in Dublin that were then collected and published in his book The Idea of a University in 1852. This was about the same time (1872) that Nietzche was railing against the deterioration of the German university system which he thought was being destroyed by what he called a “micrological” pendantry. Newman argues for traditional liberal education, that instead of seeking hyper-specialized knowledge sought to master the studium generale which he translates as the “School of Universal Learning.”

For Newman, a liberal education was its own reward, valuable for its own sake, and befitting someone who would truly be free. For Newman education was the cultivation or perfection (full development) of the intellect–“the true enlargement of the mind and the power of viewing many things at once.” He is truly eloquent on this point, offering not just a restatement of the ancient Greek ideal, but revivifying it. I quote at length, so the reader can get a sense not only of Newman’s thought, but his eloquence:

To have even a portion of this illuminative reason and true philosophy is the highest state to which nature can aspire, in the way of intellect; it puts the mind above the influences of chance and necessity, above anxiety, suspense, unsettlement, and superstition, which is the lot of the many. Men, whose minds are possessed with some one object, take exaggerated views of its importance, are feverish in the pursuit of it, make it the measure of things which are utterly foreign to it, and are startled and despond if it happens to fail them. They are ever in alarm or in transport. Those on the other hand who have no object or principle whatever to hold by, lose their way, every step they take. They are thrown out, and do not know what to think or say, at every fresh juncture; they have no view of persons, or occurrences, or facts, which come suddenly upon them, and they hang upon the opinion of others, for want of internal resources. But the intellect, which has been disciplined to the perfection of its powers, which knows, and thinks while it knows, which has learned to leaven the dense mass of facts and events with the elastic force of reason, such an intellect cannot be partial, cannot be exclusive, cannot be impetuous, cannot be at a loss, cannot but be patient, collected, and majestically calm, because it discerns the end in every beginning, the origin in every end, the law in every interruption, the limit in each delay; because it ever knows where it stands, and how its path lies from one point to another. It is the [tetragonos] of the Peripatetic, and has the “nil admirari” (nothing to surprise) of the Stoic,—

Felix qui potuit rerum cognoscere causas, (Happy is he who can understand the causes of things) There are men who, when in difficulties, originate at the moment vast ideas or dazzling projects; who, under the influence of excitement, are able to cast a light, almost as if from inspiration, on a subject or course of action which comes before them; who have a sudden presence of mind equal to any emergency, rising with the occasion, and an undaunted magnanimous bearing, and an energy and keenness which is but made intense by opposition. This is genius, this is heroism; it is the exhibition of a natural gift, which no culture can teach, at which no Institution can aim; here, on the contrary, we are concerned, not with mere nature, but with training and teaching. That perfection of the Intellect, which is the result of Education, and its beau ideal, to be imparted to individuals in their respective measures, is the clear, calm, accurate vision and comprehension of all things, as far as the finite mind can embrace them, each in its place, and with its own characteristics upon it. It is almost prophetic from its knowledge of history; it is almost heart-searching from its knowledge of human nature; it has almost supernatural charity from its freedom from littleness and prejudice; it has almost the repose of faith, because nothing can startle it; it has almost the beauty and harmony of heavenly contemplation, so intimate is it with the eternal order of things and the music of the spheres.

Atque metus omnes, et inexorabile fatum (And the fear and inexorable fate of all [death])

Subjecit pedibus, strepitumque Acherontis avari. (He throws underfoot, with the din of the greedy Acheron river)

I think I can safely say that nearly no one speaks this way today about education. To our ears, “the perfection of the intellect” is masked by the din of the Acheron River–the river of the underworld–our coming demise–or by the yelps and hoorahs of current carnival culture, with its ubiquitous distractions. What’s worse, we don’t even know what the words “perfection” and “intellect” mean as Newman uses them. To tell an 18 year-old college student that we seek the perfection of his intellect is like telling him we that we think he should “develop his cognitive capacities”–bleh.

Newman was able to restate and revivify the classical tradition in the middle of the 19th century–and he continued the great conversation about education. Who will do this in the early 21st century?

I will leave the reader with one more distinctive emphasis found in Newman: education is essentially a relationship, a friendship between student and teacher, making a university a vibrant community of learning. When we talk of education as the cultivation of virtue, we are certatinly echoing Newman (who was restating the great thinkers before him); When we talk of education as community, we are also echoing Newman. Students learn from teachers and colleagues. Humans, he thinks, are compelled by nature to engage in “mutual education”—we can’t help but to share knowledge and educate one another. The university is one evolved and grand way we do this; it is a place “for the communication and circulation of thought, by means of personal intercourse.” While the university may represent a pinnacle of learning, he argues by way of illustration that similar kinds of “university” education exist in the education of a gentleman, politician, scientist, city-dweller and catechized Christian.

Man cannot live by books alone. Newman loves books, but he regards those capable of writing books to be best at cultivating wisdom and securing an education. Why not just read great books? Newman’s answer: Why not study personally with the authors? Why not become an academic disciple? If you could study with the man and not just his books—wouldn’t you do so?

This “man to man” personal intercourse Newman calls a rival method, a method that rivals the mere reading of books, and all attempts to become a self-educated man or woman. While we admire those who have read many books and studied “on their own,” we instinctively know that a full education requires a relationship with a master. Christ said as much when he said that “a student is not above his teacher, but when he is fully-trained will be like his teacher” (Luke 6:40). Newman says the same when he argues that the life of a study “which makes it live in us, you must catch… from those in whom it lives already,” and “we must come to the teachers of wisdom to learn wisdom.”

Haven’t we all known a self-educated man or woman who lacked the deeper, living wisdom found in those who had been tutored by a virtuoso? Don’t many of us lament that while we have learned from our private reading, we long for a person who embodied those books and who could better guide, lead and teach us?

Over 150 years ago, Newman makes a case against online learning and internet research as sufficient for a full education. He notes the same objection we hear today from advocates of a wholly online education: “Why, you will ask, need we go up to knowledge, when knowledge comes down to us?” His humorous description of the “profusion of print” is similar to the contemporary laments of the profusion of distracting digital devices that have nearly replaced our real lives with virtual ones. No doubt, Newman today would exhort us to put down our smart phones and actually converse with one another, face to face, student to teacher, disciple to master. This is Newman’s rival method, the “Oral Tradition.”

Newman raises us for the question: Why have we come to college? What is it we seek at college? Most likely students enroll in collegee for several reasons—to explore new subjects, enjoy new friendships and community, prepare for a working career, to grow in wisdom. Of these good goals, should any be chief among them?

For his part, Newman privileges the communal cultivation of wisdom and knowledge as the chief purpose and “idea” of a university. The word “university” means (from the Latin) “turned into one” such that many various parts might come together in a unity. It is similar to our word “college” that is derived from the Latin collegere, which means “to gather.” A college is a gathering of scholars and students who come together in a unity qualified by excellence in the pursuit of wisdom and knowledge.

Newman mentions that universities have a kind of gravitational pull, attracting excellent thought, scholarship and interchange. If true, this means it is a great honor to attend a university and associate with such excellence, with a fair chance that we might acquire some small quantity of excellence ourselves. In fact Newman says that “excellence implies a center.” Perhaps he was thinking of the Latin root for excel, for it is excellere, which means “to rise up high, to tower.” Universities and colleges are known for their high towers that symbolize at once the quest for knowledge and wisdom, the reach for greatness, and the call for us all to gather and seek together. For many of us, it is at college that we grow up.

For further reading:

- Certainly, the reader will want to consult Newman’s The Idea of a University (1852).

- The reader may also want to read his brief essay by the same name that can be found online or in the Harvard Classics, volume 28. This essay was published in 1856 as part of a book called The Office and Work of Universities and is clearly derived from his previous book bearing the same title as the essay. This essay presents Newman’s distilled thought about the purpose and function of a university, and has become a classic description of the traditional model of university education.

It won’t surprise many of you to hear that I am continuing to read, think, and write about . . . restful learning. I am working on a new book, likely to be titled Learning from Rest, which will follow and complement Sarah Mackenzie’s

It won’t surprise many of you to hear that I am continuing to read, think, and write about . . . restful learning. I am working on a new book, likely to be titled Learning from Rest, which will follow and complement Sarah Mackenzie’s