by Christopher Perrin, PhD | Nov 5, 2013 | Book Reviews

It is at this point that Leigh Bortins is helpful. She very well knows the challenge facing thousands of homeschooling moms around the country who are educating their children classically. She knows how to start at the beginning (a very good place to start) and keep things simple, elegant and achievable. Now to use a word like “simple” to describe a book about classical education (which can be complicated and which many complicate) may sound like a criticism, but it is not. To take something big, various and complex and reduce it to its essential attributes is no easy task–it takes intelligence and self-control. I know this first-hand because I am one of those who is prone recklessly to dive into deep waters and then eagerly report what I don’t really yet understand. The recovery of the whole of classical education will take at least another generation–it is a long obedience, a a long labor of love. Bortins is wise: it turns out that homeschooling parents need a clear practical books first and foremost, and these are the kind of books she has set out to write. We need to walk before we run, and Bortins has set many to walking and walking fast. There will be time for other books and deeper learning, but the classical tradition should not be needlessly complicated–ever–but especially at the beginning.

So Bortins walks us into the tradition of dialectic, the art of asking wise questions that lead students to do the same. She crafts the book around the common topics of Aristotle: definition, comparison, relationship, circumstance and testimony) and shows how these topics or “lines of argument” can enable students to ask thoughtful questions of any art, study or discipline, essentially equipping students to engage truth, goodness and beauty wherever they are found. These common topics come from Aristotle’s Rhetoric, but they are well-suited to introduce us to dialectic. The fact that Bortins would use key content from rhetoric as key components of dialectic underscores two points: 1) Rhetoric did not (and need not) always follow dialectic. Rhetoric (aspects of it) can be taught earlier though its most prevalent place was after dialectic 2) Dialectic and Rhetoric are integrated and not completely discrete disciplines. Yes, we can use rhetorical elements (the common topics of invention) to engage in dialectic teaching. Yes, we will use logic as we engage in the teaching of rhetoric. The liberal arts can be used with great versatility–even to teach each other.

by Christopher Perrin, PhD | Nov 4, 2013 | Book Reviews

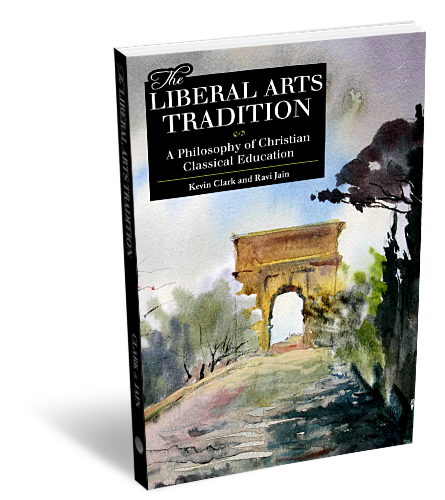

I am glad to be a part of a strong new book on classical education to be released this December. Kevin Clark and Ravi Jain have been working on a pithy book on the philosophy of Christian classical education for over five years, and taken the book through some eight versions, as they have sought critical feedback from professors, scholars and teachers. The result is a short book of about 200 pages that is remarkably clear, historically accurate and philosophically intelligent. As a general introduction to classical education, I think it is the ideal “201” book that will take readers to the next the level of understanding after reading books like Recovering the Lost Tools of Learning (Doug Wilson), Wisdom and Eloquence (Evans and Littlejohn), The Well-Trained Mind (Bauer and Wise), and The Core (Bortins). The name of the book is The Liberal Arts Tradition: A Philosophy of Christian Classical Education, to be published by Classical Academic Press this December.

Dr. Peter Kreeft wrote the foreward for this new volume (a meaningful endorsement) and I am lucky enough to write the “Publisher’s Note.” Here is my note below, posted with the hope that it may further whet your appetite for this excellent book.

A Note from the Publi sher

sher

Seeking to recover a lost art or craft is a difficult endeavor. There are few, if any, who are masters of the craft or art and who can teach the necessary skills to those coming behind. Those of us who have been trying to recover the art of classical education have been in that awkward position of trying to craft a curriculum and pedagogy without training and only a few tools. We have tried to give what we were not given ourselves. We are trying to reconstruct a bridge without having studied bridge building.

The good news is that the recovery has been underway for about thirty years now, and some good books have been written and many great old books found and read. Beyond that, there have been many who have been building bridges—actually implementing a recovered classical Christian education in our schools/homeschools and slowly learning the art, often through a good deal of trial and error. We are slowly finding our footing, finding ourselves walking more confidently on the old paths and finding the old way very much suited to our own new times. The bridge may not be beautiful, but it’s now functional and people are crossing over. Slowly the bridge is getting wider and stronger and gradually more attractive to the eye.

Kevin Clark and Ravi Jain are two educator-philosophers who have been reading the old and new books and implementing their ideas at the Geneva School in Winter Park, Florida, for some ten years—building the bridge. What’s more, they have discussed their ideas with peers and critics over this span, inviting leading educators and professors from around the country to engage and critique their ideas. In this crucible of give and take, their ideas have evolved and clarified and have resulted in this pithy, clear, and profound book, setting the model of Christian classical education before us in bright light. To those who have read Douglas Wilson’s Recovering the Lost Tools of Learning or Evans and Littlejohn’s Wisdom and Eloquence, this book will prove to be the illuminating third book that helps complete the bridge linking us back to the classical tradition of education.

I have noted that this book is pithy and clear. It is. Clark and Jain took this manuscript through some eight editions, refining the text more each time, knowing that the discussion of classical education is often confusing on many levels. In at least two ways Clark and Jain bring clarity where it has often been lacking. First, they clarify the confusing taxonomy of the classical curriculum (scope and sequence) and they define terms. They accomplish this with a historical survey of the classical curriculum as well as a contemporary survey of its application and terminology. Too often we find an unstable blend of modern terminology and traditional classical categories. Generally there is talk of the Trivium and Quadrivium—blended with many other kinds of terminology and classification. We are not sure what is specified by “art,” “science,” “humanities,” “grammar,” or “natural philosophy,” because these various words are used in different ways and already have a wide or uncertain semantic range. Clark and Jain bring much-needed clarity to this discussion.

The second way in which Clark and Jain bring clarity is by showing us the entire context of the classical curriculum—a context that is larger than the seven liberal arts of the Trivium and Quadrivium. In fact, for the first time (for many) they show us explicitly how singing, worship, poetry, recess, stories, drama, and field days are in fact an integral part of a classical education. They show us how history, literature, philosophy, and theology (not liberal arts) are critical to the tradition. They summarize that context for the integrated, holistic, and humanizing curriculum as PGMAPT: piety, gymnastic, music, arts (the liberal arts), philosophy, and theology. In my thinking, PGMAPT has already become the mental overlay I use for reflecting on the general endeavor of classical education—it is the best big picture I have seen.

This model proves to be very helpful to elementary school educators (especially in grades K-2) who do not teach Latin, logic, or rhetoric and who often ask “How do I teach classically?” Well, a Kindergarten teacher is indeed a profoundly classical teacher who helps establish young souls in piety, gymnastic, and music—priming and cultivating the affections, loves, wills, and bodies of children at a time when they are docile, receptive, and eager. It is these teachers of the young who make the first deep and lasting impression on the souls of children—tuning their hearts and training their bodies, engaging them in a holistic and essentially “musical” education, and educating them in wonder that teaches “passions more than skills and content.” It turns out that the classical primary teachers are the exalted “wonder-workers” of the school. In this respect, the primary teachers lead the entire endeavor, as “wonder” is a condition for all future study.

This model is also helpful to upper school educators who teach literature, history, theology, and philosophy. Training in the liberal arts while humanizing “goods” in themselves nonetheless prepares students for the formal study of philosophy and theology. There is a kind of biblical study that is present even in kindergarten, but the formal study of theology requires the training of the liberal arts to be done with mastery. Thus Clark and Jain say that classical education is “grounded in piety and governed by theology,” which is to say that biblical truth is both the beginning and the end (the arche and the telos) of Christian classical education. This recovered full model of classical education (PGMAPT) gives the twelfth-grade theological educator his rightful place. Though the formal study of theology comes last in the sequence, she nonetheless is the governess guiding the entire educational enterprise, giving coherence and unity throughout—the “queen” of the arts.

If recovering classical education is like recovering a lost art, it might also be like trying to remember a hazy dream. In the reading of dozens of books on classical education, I often experience the exercise in a kind of dream state. I find myself catching glimpses of things that I know are part of a great whole, as if I once knew that whole but can’t quite remember it. When another book restores some part of that whole, I put that part into place with a flash of recognition—as it fits into place I recognize that I once knew it. Who will restore to me the whole? How can I remember what I once knew? Well, Clark and Jain have helped stir these collective memories, telling us who we once were, restoring our narrative, restoring our rightful inheritance. How do they do this? Over ten years they have somehow succeeded in remembering who we all once were and they can now tell the story that awakens us. PGMAPT is that story, and I think you will immediately recognize it as your story, as the education for which you have yearned and want to give to your children.

—Christopher A. Perrin, PhD, Publisher, Classical Academic Press

by Christopher Perrin, PhD | Jun 12, 2013 | Articles, Book Reviews

The Abolition of Man–A Review for Classical Educators

C. S. Lewis

The Abolition of Man was first published in 1947, just two years after the end of the second World War, after a great deal of abolition indeed. Lewis’ book, however, is not about man’s abolition by bombing and battles, but by grammar books and teaching methods. Eventually he does address propaganda (think Nazi propaganda) and conditioning as the eventual teaching method employed by a controlling state.

The Abolition of Man is one of C. S. Lewis’ smaller books. It is not, however, a small read. In this little book, Lewis seeks to swim upstream into a very brisk current, and one feels the pressure of that fight and the strong push against Lewis’s thought that exists everywhere today, as it did a generation ago when he wrote it.

When I read The Abolition of Man—and I have read it some five times—I find myself in the water with Lewis, kicking for all I am worth. Then occasionally I feel myself sliding downstream, for modern thought about education and “values” has a pull on me at times. The essence of his book is straightforward: there is a real, knowable world with objects that merit our blame and praise. At one place Lewis calls this the doctrine of objective value, though he also uses “The Tao” for shorthand.

How can that seemingly self-evident truth make for such a hard, brief book? Well for one this doctrine is attacked indirectly at every side so that we have been conditioned to resist it; secondly the denial of this doctrine leads to several ideas and practices that at first, don’t seem related, but in fact are. Finally this book is a hard read because we need its wisdom so much, but have employed it so little. Lewis makes a compelling case for cultivating the affections of our students, but we have largely taught our students the way were taught—too often encouraging our students to invent their own moral universe.

Lewis makes an argument for objective value, not by quoting biblical texts, church fathers or theologians, though he could. He does not quote philosophers of aesthetics, though he could. He appeals rather to the universal consensus of the major world religions and moral or ethical philosophy. Though he is a Christian, he makes an appeal merely as a theist, pointing out that theists of all kinds recognize and confess that their exist objects in the world (like mountains, trees, sunsets, waterfalls) and real human qualities (like courage, generosity and self-sacrificing love) that merit our praise and accompanying emotions of gratitude, admiration and love. As well, the universal tradition recognizes and confesses that there are some objects in the world (like deformity and destroyed landscapes) and some human qualities (like thievery, lying and cowardice) the merit our blame and accompanying emotions of revulsion, anger and sorrow.

If you assent to this doctrine of objective value, you may hold to it on rational grounds as you think about it just now. But isn’t beauty in the eye of the beholder? Do you confess (at times) “to each his own” and “live and let live”? Are not your reactions to many objects and qualities actually—your reactions? They may not be my reactions, for I am a different person than you with a different background, different training, different assumptions and preferences. We both see the storm approach and lightening strike. “The glory of God and his power!” you may say. “No soccer game today!” I may say. Are not “value judgments” largely (or at least significantly) subjective? If you feel the force of this suggestion, then you are in common company, first because we have all been conditioned to think that all value judgments are subjective and second because there is some truth to the suggestion (we all bring personal biography to our assessments in varying degrees). The truth in it, combined with our incessant conditioning (which distorts the truth in it) makes reading Lewis’ book a challenge for many of us.

For a classical educator, things can get more complicated yet, when we read that classical tradition from Plato onward tells us that we must cultivate the affections and sensibilities of the young to love that which is lovely even before their age of reason. This is truly alien to our culture: we must train the emotions of children to love the good and beautiful and hate the bad and ugly. What? Isn’t this indoctrination? Isn’t this imposing our view of what is true, good and beautiful on someone else—and a vulnerable, impressionable child at that? Don’t we need rather to encourage the young child to seek out her own preferred good and bad things, find her own style of beautiful and even her own truths? How dare we stunt or destroy this child’s freedom to choose her values and become what she wishes!

Well Lewis, Plato, Aristotle and Augustine all say that we should do precisely that. The true, good and beautiful are real and knowable and should not only be presented to children, but they should be encouraged to love the true, good and beautiful. Their emotions should be cultivated so that they blame and hate the false, bad and ugly as well. Are you kicking upstream? Slipping a little?

Now note the related implications. If you accept the doctrine of objective value and you are a teacher, should you not regularly show forth what you regard as universally true, good and beautiful objects and acts? Should you not seek to “order the loves” of your students and exhort them to flee disordered loves for those things that are not true, good and beautiful? Is there anything beautiful in your classroom—or your manner of speech? Are you full of admiration and praise, and then in proper measure full of blame and critique? Or is everything you teach left in a mush for students to sort out and think as they wish?

Because we have been conditioned to resist calling something truly lovely and then loving it, we often lack the courage to praise, extol, admire and praise. We also lack the courage to blame the ugly, despise the lie, flee the immoral. We have become humans without robust emotion, without conviction, without affections, without heart. In Lewis’s words, we have become men without chests.

But the implications of the doctrine of objective values travel in another direction too. If one rejects this doctrine, what happens to education? How will we teach? Well wittingly or not, certain things follow, or eventually follow. If all value judgments are merely subjective, then we merely describe our feelings when we make such judgments—which amounts to nothing particularly profound. Thus when our student Susan says, “That horse is beautiful” she merely states that she has certain pleasant feelings when she looks at the horse, but says nothing objectively real about the horse. What this does to teaching we have all seen and experienced. Teaching to a large extent becomes a group exploration of our individual reactions, responses and feelings, often celebrated as our individual, autonomous freedom. Instead of celebrating something as universally lovely, we celebrate the individual, free student and his opinions; each child is a unique snowflake (just like every other student). What we don’t realize is how profoundly this view has affected us. Do you feel the current? Don’t we all want to tell our children they indeed are unique and wonderful? Aren’t virtually all their ideas to be admired and encouraged? Don’t you want to view your own ideas, inclinations and opinions in a similar way? We have been carried down this river for many years.

If a teacher does not believe in object value, it does not mean that he won’t teach values. Lewis argues that the teacher who denies such values will in fact teach a very clear set of values—and they will be the prevailing values of “his set” the assumed values of the modern establishment of which he is a part. Even the denial of objective value is itself a value after all—a confessed common good. Lewis’ point is that all humans will hold to universal values—even those denying them. Such values will be hidden and assumed by such teachers, however.

Lewis concludes his book, by pointing to an ominous implication of rejecting the doctrine of objective value. If there is no objective value, then our educators will eventually become our conditioners, conditioning us to states of mind convenient to the aims of those in power. It will employ pervasive propaganda and various forms of coercion. There is simply no other means of appeal to persuade people to a course of belief, action or behavior. If there is no objective value, and we are unique and free to feel as we wish, how will we ever act in concert toward the same ends? A million autonomous snowflakes will not drift into a civilization. If there is to be a cohesive society (without objective value) then it must be conditioned and forced. A state-sponsored indoctrination follows in which humans are manipulated into serving the state’s interest even if this means the abolition of the chest and heart of man, or the abolition of man himself.

The subtitle of Lewis’ book is “How Education Shapes Man’s Sense of Morality.” We educators are indeed shaping the souls of humans beings, shaping them to love one thing or another. As we read, and re-read this profound little book, we should pay attention to the way in which our own poor education has shaped our sense of morality—our sense of what is true, good and beautiful. And since we are swimming against the current, we should do so together and kick, kick, kick.

Questions for educators:

- Are you reluctant to praise the true, good and beautiful before your students?

- What “hidden” values do you assume that come through indirectly in your teaching?

- What are the hidden values in your school culture and community?

- In what ways does the subjectivist view of morality linger in your teaching or school community?

by Christopher Perrin, PhD | Aug 5, 2011 | Articles, Book Reviews

Waiting for Superman (Paramount Pictures)

Christopher A. Perrin

It is hard to watch David Guggenheim’s documentary Waiting for Superman without leaning into the screen with anticipation and hope, only to droop with disappointment, yes even despair. It is the kids that do that to you—real children with real dreams, bright and earnest, brimming with surprising potential, supportive parents or grandparents, hoping and praying they can be one of the few selected (by lottery) to attend a promising charter school. They don’t get in (with two exceptions).

Daisy is a Hispanic elementary student from a challenging section of Los Angeles (East LA). The camera follows her for most of a year, recording her at school and home diligently studying, talking excitedly about her dreams to be come a veterinarian. After watching her for a few months, you have no doubt she could become veterinarian (or just about anything else.). Her extended family pulses with her potential, believes in her, as you do. If she stays in her public school system, her chances of going to college are virtually nil. A local charter school offers hope—the camera reveals the charter school is doing excellent work and could keep her on her dream’s path. After getting to know Daisy and her family, you watch her sitting in the public lottery, fingers crossed, with hundreds of other students all vying and praying for one of the few spots at the school. She doesn’t get in. She will have to attend her local middle school, which has a 40% graduation rate (from eighth grade). And so it goes with several other hopeful students followed by Guggenheim’s camera.

The film gives the impression that Guggenheim is no natural critic of public, government education and that perhaps he would have liked to put his own children in a public school in Los Angeles. Diane Ravitch (in her critical review of the film: http://www.nybooks.com/articles/archives/2010/nov/11/myth-charter-schools/?page=1) points out that Guggenheim himself attended Sidwell Friends, an elite preparatory school in Washington, D.C. (Obama’s children attend Sidwell). Whatever his predispositions toward public education, when his children became of school age he simply could not seriously consider enrolling his children in the local public school. For him, the raw data was persuasive: too many students were getting lost in the school system, unable to realize their academic potential, far too few even graduating from high school (in some cases below 20%). What was going wrong inside these schools? He set out to find out and produced Waiting for Superman (he also produced An Inconvenient Truth, about global warming) and enrolled his children in a private school—because he could afford to.

What goes wrong in these schools is nothing new to anyone even generally familiar with urban, public education. Bad teachers can’t easily be removed. Even with significant funding, good books and supplies are scarce (and often poorly treated or destroyed by students). Students disrespect teachers and teachers endure students. Resolute administrators become disillusioned and give up, or become opposed (by powerful teacher unions) and forced out. Schools lack a culture of study, rigor, discipline or optimism and instead become soul-squelching institutions dominated by popular youth culture and the culture of the street. All this is nothing new. What is new is what the eye of the camera reveals. We don’t just hear it, we see it, and we see the Daisys of the world being lost.

We also see some remarkable people working for change. Michelle Rhee (former superintendent of Washington, D.C. schools tell us of her experience trying to reform one of the worst-performing school districts in the nation. She worked valiantly, was opposed venomously, then removed when a new mayor was elected (campaigning that he would remove her if elected). Rhee concludes that the biggest obstacles to reforming the D.C. district is not money or curriculum but the teachers themselves (not all, perhaps not most, but enough) who are more concerned with their job security (tenure) than students and their welfare.

Another administrator with Kipp charter schools (http://www.kippny.org/) is doing noble work providing a superb education to minority students in Harlem. Kipp seems to prove that poverty does not keep students from an excellent education—bad schools do. The Kipp charter school in Harlem has a 96% graduation rate. Guggenheim notes that he used to believe that bad (poor) neighborhoods made for bad schools. Now he believes bad schools cause bad neighborhoods.

Who is waiting for Superman? The children are, and it appears he is not coming. These students need rescue—rescue from their failing, dis-affecting, de-humanizing schools. If there are any heroes in the film it is the courageous administrators and teachers of several charter schools that have been started and succeeded (almost against all odds) right amidst a ring of failing schools. Clearly, Guggenheim thinks we must offer students like Daisy something different and better, like innovative charter schools. After watching the film it is hard to disagree.

However, even great charter schools lack something vital—the freedom to engage the culture of the Christian west and her queen, theology. We must settle for a secular rigor and an eclectic and unstable curriculum. Put another way, we must settle for getting urban kids to suburban standards. Still secular, still likely encumbered with all the challenges of our better suburban public schools, but still better.

As well, we must ask ourselves if Guggenheim is telling all the critical parts of the story. He admits that only one in five (20%) charter schools are succeeding. He does not show any examples of successful public schools in urban settings. He chooses not to tell us the remarkable amount of money that is spent at some of these charter schools (in his film) that receive public and private funding. The organization that runs the Kipp schools, for example, has over $200 million in assets and provides students with an extensive array of social and medical services. The boarding school featured in Washington, D.C., spends $35,000 per year on each student. In other words, the charter schools that Guggenheim features are funded well beyond typical public (and private!) schools. With this kind of funding, can we really regard such students as impoverished? Diane Ravitch (a prominent historian of education) points to studies that show that only 17% of charter schools are out-performing comparable public schools, that 37% are performing worse than public schools and that 46% are performing the same as public schools.

Ravitch thinks that Guggenheim is engaging in artistic propaganda and special pleading, even while highlighting urgent problems and some remarkable successes. For Ravitch, poverty is a chief causal factor contributing to student performance and thus school achievement. What she doesn’t make explicit (but seems to assume) is that urban families are in crisis and in fact disappearing as in-tact supportive communities. Without a supportive family, a student can rarely succeed in a public, charter, private or classical Christian school. Now there is a relationship between poverty and family cohesiveness, but being poor (as hard as that is) does not cause the disintegration of a family. Poverty is not, per se, a sin nor does it cause sin, though it brings its peculiar temptations even as wealth does.

Something beyond mere poverty is at play, destroying American families, not only in the cities but in the suburbs. Urban families, however, are clearly in greater crisis and no doubt poverty is exacerbating the family breakdown. Leaving aside, for the moment, the complex nexus of factors making war on the American family, we should remember that schools can teach but not single-handedly resuscitate a family dying from a hundred wounds. Not even great classical Christian schools. Schools cannot effectively serves as social welfare agencies, health care providers, churches, or surrogate mothers and fathers. As Jacques Barzun pointed out long ago (in Teacher in America), schools can teach but not educate, for to “educate” requires a congenial collaboration among parents, families, friends, supporters, churches, teachers, administrators and students. Ravitch notes that all the families in Waiting for Superman are supportive and invested in the education of their children (special pleading again). The reality is that far too many families are broken and unable to support and encourage their children generally, much less follow and support their education. Guggenhiem seems to think that a local charter schools can change all this. He thinks, in fact, that it is failing schools that make for failing neighborhoods—as if the local school has done the most to cause the breakdown of urban culture and families.

Causation (as philosophers and scientists will tell us) is tricky and hard to pin down. Our urban culture is suffering on account of multiple causes in my view, not the least of which is the ubiquitous, invasive influence of secular mass media that is shaping the souls of our American youth in and out of the cities. James K. A. Smith has pointed out the various ways “secular liturgies” from the mall to the athletic field to the movies to Facebook are powerfully forming our youth to love a secular ideal of human flourishing much different that the New Testament ideal of the Kingdom of God (Desiring the Kingdom: Worship, Worldview and Cultural Formation). Which leads me to say that without the revival of city churches urban schools (of any stripe) will have a greatly diminished impact. A great urban school cannot do all that is needed. In fact an urban school can only become great when urban churches support it and compliment it with their own vibrant ministries to families. Christian educators cannot flee to schools as the best means of reviving our urban youth and families. Rather churches, schools and families must form vital partnerships if there is any hope of creating culture and cultivating students not just as future workers but human souls.

Private Christian educators should take note of Guggenheim’s film, but view it critically. He does engage in special pleading, generalizing and one two many straw men. He does not assess the vital role of supportive families or churches in providing education and supporting local schools. His use of statistics has been questioned (effectively by Ravitch). He does, however, powerfully portray the sad state of many urban public schools and the plight of many urban youth, who at present have no choice but to attend a school that will fail them as it has others. By providing a few shining examples of remarkably successful charter schools (even if very well-funded), he suggests it could happen again and elsewhere.

Christians should not wait for public funding or a public charter to offer hope to Daisy and thousands like her. While it will take immense sacrifice of time and resources, it is now time for the accrued wisdom and experience of the last 30 years of renewing classical and Christian education to be brought to bear to start schools in all the major cities in the U.S. This is already beginning to happen, but needs to extend and expand. The Oaks Academy (http://www.theoaksacademy.org/) in Indianapolis, IN is providing a superb liberal arts education to students in that city. Logos Academy of York, PA (http://www.logosyork.org/) is doing the same there. Mortimer Adler quipped that best education for some (meaning a robust liberal arts education) is the best for all. Some of us have been able to afford to give a recuperated, if imperfect classical education to our own children. Are we now ready to give it to others who otherwise will never receive it? They are wanting and waiting

by Christopher Perrin, PhD | Mar 15, 2011 | Audio, Book Reviews, Interviews & Podcasts

Many readers of this blog may recall my review of the book Desiring the Kingdom: Worship, Worldview and Cultural Formation by James K. A. Smith who is also an associate professor of philosophy at Calvin College. I like the book immensely, and think that Smith has articulated better than anyone else in modern times how humans are shaped and–if you will–what humans are for. According to Smith, humans beings cannot help imagining an ideal of human flourishing and in fact, imagining ideals is a large part of what it means to be human. Smith contends that we are all seeking some version of the good life, we all desire a kingdom. What is more, we are all being shaped and formed in various ways to love and desire one sort of kingdom or another.

Now all this has profound implication for education, for whatever else education is, it is a sustained attempt to shape and form a human being. Even when educators have no idea what ideal or form they hold forth–they are shaping and forming nonetheless, for education occurs directly and indirectly, for better or for worse.

Several leaders in the renewal of classical Christian education noted this book when it was published in 2009, and immediately saw its relevance to the renewal. Among those leaders was Bob Ingram, headmaster at the Geneva School of Orlando. After reading the book on a plane flight, Ingram decided he had to have Smith come visit his school and address his faculty. When I heard that Smith was coming to Geneva, my colleagues and I at Classical Academic Press offered to fly down to Orlando and record Smith. We did that in October (2010) and can now post the results of that fruitful interview here on this blog. While we recorded him on video and audio, the audio clips are listed below–we will release the video clips later this spring. Many thanks to Bob Ingram of the Geneva School and to Geneva educators Ravi Jain, Kevin Clark and Grant Brodrecht who with Bob conducted the interview with Jamie Smith.

The entire 45 minute interview can be heard by clicking on the link entitled “Jamie Smith Interview on Classical Education.” Alternatively, you can listen to any individual segment from the interview by clicking on the other links listed below. These individual clips average about 5 minutes in length. Enjoy.

James KA Smith Interview on Classical Education (entire interview-45 min)

James KA Smith Pedagogy Assumes an Anthropology

James KA Smith How Humans are Shaped

James KA Smith The Problem with Worldview Education

James KA Smith Secular Liturgies

James KA Smith Countering Secular Liturgies

James KA Smith How Christian Schools Are Secular

James KA Smith The Church and Christian Education

James KA Smith Pastors and Classical Christian Education

James KA Smith What Secular Education Lacks

James KA Smith Humans as Thinkers Believers and Lovers

James KA Smith Postmodernism and Classical Christian Ed

James KA Smith Neuroscience and Character Formation

James KA Smith Education, Culture and The Arts

James KA Smith Advice for School Administrators

by Christopher Perrin, PhD | Nov 24, 2010 | Articles, Book Reviews

Leisure is not the cessation of work, but work of another kind, work restored to its human meaning, as a celebration and a festival.

–Roger Scruton

We Americans have no trouble being busy. American educators are about the busiest people I know. Classical school administrators are usually frenetic. Teachers work so hard for nine months that they truly do need a summer’s rest. How do classical students fare? Well, they need those three months of summer too.

I was interviewing Ken Myers of Mars Hill Audio recently, and asked him what he would hope to see if he observed a classical Christian school. I was braced by one of his responses: he would hope to see a rhythm of fasting and feasting. Fasting and feasting sounds strange to 21st century American ears, though it ought not sound so strange to American Christians trying to learn from the classical tradition. The church has practiced fasting and feasting for centuries. For various reasons, many, perhaps most, American Christians have forgotten these practices—and so we are not likely to quickly bring them to our schools.

Ken’s comments got me thinking again about our need to re-examine and understand leisure, contemplation and rest as vital aspects of a classical education. Contemplation, after all, is a key component of the classical tradition of education. Do our students have appropriate time to reflect on what they read and to contemplate the great ideas of the Great Conversation? Or do they fly from book to book, class to class and grade to grade? Ah, we are Americans and we are busy seeking ways to keep the cake and eat it too. We want depth and breadth. We want music, sports, art, drama, debate, trips, labs, language, science, literature, logic, rhetoric, theology, history and a dozen electives. It is not unusual for a student to be tracking 7-8 classes plus several extra-curricular activities. Parents need sophisticated planning software just to manage transportation of students from one place to another. Parents too are often frenetic.

The things we are busy about deserve scrutiny. Our history is one of sustained, hard work, forging a country out of wilderness, building cities, moving west and building more cities. We are widely known for our “can do” spirit and seemingly endless entrepreneurial energy. Classical leaders and educators possess this strength. What we don’t do well is rest.

In 1948 the German philosopher Josef Pieper wrote a small book (about 130 pages) entitled Leisure the Basis for Culture. Classical educators need this book. Pieper does more than tell us we need to slow down and take a breather. Rather, he helps recover the long-lost meaning of the word leisure. In a society that greatly values “work for the sake of work” leisure has come to mean time free from the obligations of work, time that most Americans often fill with amusements and play. This is not the leisure of long ago.

Pieper points out that the Greeks and Romans did not even have specific words for “work” as a positive concept. The Greeks referred to “work” as ascholia which means “not at leisure.” The Greek word for leisure is schole, from which we derive our word “school.” Astonishingly, the Greek word for institutions of learning means “leisure.” The Romans’ word for leisure is otium and their word for work is neg-otium (not at leisure), from which we get our word “negotiate.” Aristotle writes “we are not at leisure (ascholia) in order to be at leisure (schole). Pieper also notes that engaging in the reflection of truth and virtue (the vita contemplavita) is the “highest fulfillment or what it means to be human” and thus of profound importance.

Now this is worth some…reflection. The classical tradition of education regarded a “school” as a place of schole. The Romans imported schole into Latin as schola, from which we get our word “school.” Just what about our schools is schole? Would our students describe our schools, among other things, as a place of leisure? This would not mean of course, that our schools would be places of mere relaxation, but places of reflection, conversation, celebration and feasting. Sound like your school?

What the Greeks and the Romans discerned as fitting for man is also confirmed by biblical teaching. When God rested after six days of creation, he was not tired. He celebrated and blessed his creation (Gen. 2:3). The Sabbath rest and the regular feasts were not given so that God’s people would do nothing, though it did mean ceasing from typical daily labor. Rather it was meant as a time for a particular kind of robust activity—feasting, celebration and blessing. The Sabbath rest is not the mere cessation of labor, but the orientation of the human to his highest end—the “work” of leisure, the “work” of praising, serving, feasting and blessing.

When C. S. Lewis studied as an adolescent with the retired Scottish schoolmaster (whom Lewis called “the Great Knock” in Surprised by Joy) he studied two subjects for three years—Latin and Greek. But wait–through his study of Latin and Greek he studied history, literature, philosophy, poetry, grammar. And he learned dialectic, because the Great Knock argued with him about everything. Lewis goes on to criticize modern education for denying students in secondary schools the hope of ever mastering anything—we cover too many subjects all at the same time to ever hope of mastering a single one. Lewis regards this as costly sacrifice, because he thinks that mastery of one subject creates a kind of confidence that leads students to go to master the next subject, now believing (and knowing) that mastery is possible.

This all flies in the face of our typical understanding of a broad-based liberal education—or does it? Dorothy Sayers suggests that at the age of 16 a classically-educated student should be ready to specialize in a subject he or she has grown to love and prefer. I think we may be caught in a false dilemma of thinking we must choose between two extremes of either a highly specialized education (study only Latin and Greek!) or studying eight subjects every semester for about ten years. As we re-imagine what form classical education should take in 21st century America, I think we would do well to ask ourselves in what ways we may have simply taken some aspects of the contemporary progressive model (eight subjects every semester plus extra-curriculars) into our schools without sufficient scrutiny. The medieval maxim of non multa, sed multum (not many but much) should be reconsidered for modern application to our schools. If we do this while also recovering leisure, perhaps we will create schools of schole that offer 21st century America something it sorely needs.

In what ways does your school pursue leisure? I would love to hear. Here are some preliminary ideas:

- Have students read fewer books in literature courses to include in-depth discussion and reflection upon them.

- Consider block scheduling: This enables classes to meet longer and facilitates discussion

- Consider a trimester schedule with only four courses: This allows students to study fewer courses at a time, more intensively, but over three semesters instead of two.

- Incorporate conversation about ideas into the school at large: Socratic circles for student discussion worked into classes; Socratic circles in which staff discuss ideas in front of students; Socratic circles involving parents, students and staff at various times and events in or out of school.

- Feasts and celebrations that integrate with the church calendar and incorporate skills and themes from student learning.