by Christopher Perrin, PhD | Feb 7, 2014 | Articles

Scholé in The Scriptures: Choosing What Is Better

Those of you who know this blog (or anything about me) know that I have been reading and writing about returning scholé to our schools and homeschools for about three years now. Here is a brief article relating the Greek concept of scholé to the Old and New Testament.–CP

Aristotle and Scholé

Well it was Aristotle who first described the importance of scholé (leisure, restful learning and conversation, contemplation), and yet the Hebrew Scriptures (which predate Aristotle) seem to touch on this theme as well. The New Testament certainly does too in some unique ways.

Aristotle writes in Book VII of the Politics:

…we fulfill our nature not only when we work well but when we use leisure (scholé) well. For I must repeat what I have said before: that leisure is the “initiating principle” of all achievements. Granted that work and leisure are both necessary, yet leisure is the desired end for which work is done; and this raises the question of how we ought to employ our leisure. Not by merely amusing ourselves, obviously, for that would be to set up amusement as the chief end of life. (Book VII:iii)

Aristotle does not disparage wage-earning work, but he says that such work (and amusement) cannot be fitting ends for human aspiration and life. The highest end is the right employment of scholé.

Scholé in The Old Testament

Now this insight was picked up by the church (many centuries later) and identified with contemplation. This is not surprising since the Old Testament also suggests a life of “restful learning” and contemplation as the heart of a full human life:

One thing I ask of the Lord, this is what I seek: that I may dwell in house of the Lord all the days of my life, to gaze upon the beauty of the LORD and to seek him in his temple. (Psalm 27)

This is what the Sovereign Lord, the Holy One of Israel, says: “In repentance and rest is your salvation, in quietness and trust is your strength, but you would have none of it. (Isaiah 30:15)

I have no peace, no quietness; I have no rest, but only turmoil.” (Job 3:26)

The Hebrew concept of shalom (often translated “peace”) also includes a connotation similar to scholé: In addition to the idea of safety and soundness, shalom also frequently means quiet, tranquility and friendship—all components of scholé.

In the Greek translation of the Old Testament (the Septuagint) scholé only appears twice (in Genesis 33:14 and Proverbs 28:19) and means leisure in the primary sense of “going slowly” (Genesis 33:14) and even wasting time (Proverbs 28:19). In the Wisdom of Sirach however, we find this interesting passage:

The wisdom of a learned man cometh by opportunity of leisure (scholé): and he that hath little business shall become wise. How can he get wisdom that holdeth the plough, and that glorieth in the goad, that driveth oxen, and is occupied in their labors, and whose talk is of bullocks? (Wisdom of Sirach 3:24, 25)

Here the word scholé is used very much as Aristotle uses it, and the context makes it clear that wisdom comes from the man who takes the opportunity of scholé and does not over-indulge in wage-earning labors. Note how the passage not only addresses too much business or labor—but also address the mental preoccupation of the man who only talks about his work. If his only talk is of his bullocks, we must surmise that his only thought is about them as well.

Scholé in the New Testament

In the New Testament (written in Greek), scholé only occurs a few times. Scholé can refer to a lecture hall (where scholé or learned discussions occur) and this is what we find in Acts 19:9 where we read that Paul took his disciples daily for discussions at the lecture hall (scholén) of a man named Tyrannus. In 1 Cor. 7:5, Paul writes that married couples should devote (scholaséte) themselves to prayer. Paul here uses the verbal form of scholé that means to have rest or leisure, or to be dedicated or devoted (no distractions or obligatory work!).

Beyond the actual use of the word scholé, we do find the New Testament addressing the concept of scholé in several places:

The Example of Christ

The first indication we get that Jesus condones “restful learning” is that time we find him at age 12, away from his parents for at least three days, “in the temple courts, sitting among the teachers, listening to them and asking them questions.” (Luke 2:46). Leaving aside the fact that “everyone who hear him was amazed at his understanding and his answers” (2:47), we should note that Jesus spend three days (sleeping at the temple too?) engaged in conversation with the best teachers in Israel. And he did this at the age of a 6th grader. He tells his parents that “he had to be in his Father’s house” (2:49), but we note that what he was doing in his Father’s house resembles scholé or restful learning.

We find Christ frequently going off by himself to pray, even for 40 days at a time. Christ seemed never to be in a hurry, but relaxed and peaceful. Even when others around him are frenetic, he is tranquil. In Luke 10, Martha implores Jesus to tell her sister Mary to help her with dinner preparations, for Martha was busy working while Mary was sitting and talking with Jesus. Jesus responds to her: “Martha, Martha you are anxious (busy) and troubled about many things, but only one thing is needed. Mary has chosen what is better (literally “the good part”), and it will not be taken from her.” (Luke 10: 42)

It is hard to imagine a better illustration from the gospels about what scholé means than this event recorded in Luke 10. We all have to prepare meals, do dishes and work for wages—and these are good things. The better thing, however (when we are free to chose), is to talk with a master. Mary was talking with the Master, and certainly chose wisely.

Example from Paul’s Writings

Paul writes in 2 Cor. 3:

Now the Lord is the Spirit, and where the Spirit of the Lord is, there is freedom. And we all, who with unveiled faces contemplate[a] the Lord’s glory, are being transformed into his image with ever-increasing glory, which comes from the Lord, who is the Spirit. (2 Cor. 3: 17. 18)

Paul notes that the faithful, in the context of the freedom given by the Spirit, contemplate (gaze, reflect) the glory of God and are then transformed to resemble that very glory. This reminds us of Christ’s teaching that a student, when he has been fully trained, will be like his master (Luke 6:36). Paul also hints that this transformation is a process that takes time. We gaze and study the glory, and slowly (with ever-increasing glory, literally “from glory to glory”) we grow to resemble this glory.

Paul has in mind the experience of Moses coming down from Mt. Sinai after meeting with God there, having received the two tablets containing the Ten Commandments. When Moses came down from that mountain, his face was glowing brightly enough that he spooked the Israelites and had to put a veil over his face.

When Moses came down from Mount Sinai with the two tablets of the covenant law in his hands, he was not aware that his face was radiant because he had spoken with the Lord. When Aaron and all the Israelites saw Moses, his face was radiant, and they were afraid to come near him… Then Moses would put the veil back over his face until he went in to speak with the Lord. (Ex. 34:29, 30, 35)

Apparently to Paul, the life of the Christian is to be one of contemplation and gazing—looking on the same one that set Moses face aglow. This implies undistracted gazing, focus and….time. Looking, gazing, contemplation thus become a metaphor for learning, conversation and transformation. After all, Moses was not upon the mountain in a kind of dream sleep—he was rather talking and listening to God—having a remarkable conversation with the Master. Paul suggests that we can now do the same.

Conclusion

It seems that even when not using the word scholé, that the Old and New Testaments nonetheless describe a growing and learning process that is very much in keeping with Aristotle’s use of the word. Slow, restful, conversation and learning is set before us as an example to follow, with Christ himself as the Master of scholé.

If the entire Christian life can be summarized as a kind of slow and sanctified conversation with the Master, could it be that all of our learning should take a cue from this same kind “restful learning” and resemble a refreshing and ongoing conversation?

If Christ says “Come to me, all you who are weary and burdened, and I will give you rest,” and if he says, “ Take my yoke upon you and learn from me, for I am gentle and humble in heart, and you will find rest for your souls,” (Matt. 11: 28, 29) then should not the way we educate our sons and daughters be gentle and restful?

How many of us have been busy about many things, thinking that we were not free to choose anything else?

by Christopher Perrin, PhD | Dec 10, 2013 | Articles

Classical Academic Press (of which I am a part) has launched a new online academy called Schole Academy. Naturally, some want to know what schole means, and sense it has something to do with school. Well it does and it doesn’t, it turns out. Here is the first essay of three on the recovery of schole in education.

Classical Academic Press (of which I am a part) has launched a new online academy called Schole Academy. Naturally, some want to know what schole means, and sense it has something to do with school. Well it does and it doesn’t, it turns out. Here is the first essay of three on the recovery of schole in education.

My friend and colleague Andrew Kern (of the Circe Institute) once hosted a conference with the theme “A Contemplation of Rest.” This was several years ago, but Andrew deserves credit for raising the banner of a problem we all know something about: Modern education is an education in anxiety. Modern administrators, teachers, parents and students are frenzied and frenetic. Students rush to classes (at the sound of bells), often eight classes a day, then run to practices, music lessons and other activities. Then a night of homework when they try to manage assignments for their eight classes for which they receive numerical assessments, often on a weekly basis. Most students by junior high fall into the all too familiar cram-pass-forget cycle of “learning” that has afflicted almost all of us during our own education. We have all taken courses, the content of which faded into oblivion just a few months (or weeks) after we completed them. Some of us can barely recall if we even took a course in say, American history or British literature.

Well the good news is that for about thirty years there has been a steady push against this kind of frenetic, ephemeral education and a curious inquiry into the kind of education that preceded this unsettling schooling that dominates America. What came before it was the so-called classical model, itself multi-faceted but still a coherent, integrated approach to education that while rigorous, was slower and more contemplative. The classical tradition of education was (and is) many things woven together: a curriculum (including the seven liberal arts), a community (yes it does take a village) and a pedagogy (from chanting in younger grades to Socratic discussion in older ones). It is a large tradition and I can heartily recommend that readers consult the new book by Kevin Clark and Ravi Jain, The Liberal Arts Tradition: A Philosophy of Christian Classical Education.

However, an important part of the tradition is contemplation itself. It would not have been conceivable to our forebears to consider a daily schedule of eight different classes, nor even the prospect of choosing a “major” field of study until the liberal arts were mastered. There were no majors in college until about the mid-1800s. Education in the classical tradition was rigorous, but it was slower, and focused on fewer arts at a time to ensure mastery and permanent learning. There was no “gaming the system” or the test; students were taught by masters who got to decide when a student was ready to proceed to further study. Teachers were expected to be masters who could be trusted to teach (because they were masters)—not functionaries of a system that forces all teachers to use the same techniques at the same time and verify their compliance by machine-readable multiple choice instruments.

Contemplation—do we even know what it is? And once we recover an intellectual grasp of it, do we know how to engage in it? Can we even slow down enough to read a long poem without getting distracted and fidgety? Have we become trained and habituated to constantly move, shift and flux—in body and mind?

The Greek word for leisure is schole (skoh-LAY). It does not mean leisure in the American sense of relaxing on a vacation at the beach. It means rather “restful learning” that comes from discussion, conversation and reflection among good friends. For the Greeks, this was the noble thing—one of the highest activities of human existence. The Greeks had another word for that kind of work that we all must do to earn our bread: ascholia. Ascholia means that necessary activity that keeps you from schole. Now wage-earning is a fine and noble thing in its own right, properly conceived. But do you see that schole is a higher thing still? Until we do, we won’t have it because we won’t want it. The classical tradition esteemed it and sought and so should we.

I close with an irony. Yes, we do derive our word “school” from schole. Schole moved into the Latin as schola (with some change of meaning) and then into German as schule and English as “school.” By the time we get to English, the restful connotation of schole has vanished. We can hope, however, that the renewal of classical education will put the schole back into school.

by Christopher Perrin, PhD | Nov 22, 2013 | Articles, Seminars & Lectures, Videos

Josef Pieper in his book Leisure The Basis of Culture says that education (philosophy and poetry for that matter) begins in wonder. Kevin Clark and Ravi Jain in their new book, The Liberal Arts Tradition, also note that in the classical tradition, education moves from wonder to worship to wisdom (the three W’s of classical education). Can a student truly be a student if she is not compelled to wonder at the startling world into which she was born? A. G. Sertillanges (in The Intellectual Life) says,

Every intellectual work begins by a moment of ecstasy; only in the second place does the talent of arrangement, the technique of transitions, connection of ideas, construction, come into play. Now what is this ecstasy but a flight upwards, away from self, a forgetting to live our own poor life, in order that the object of our delight may live in our thought and in our heart.

Now by ecstasy, Sertillanges is appealing to the literal meaning of the Greek word ecstasis, which means to be lifted up and out of the ones “station” or the place where one is fixed, standing. Children are naturally set to wonder and delight in truth, goodness and beauty–and they are easily cultivated to continue in wonder. Do we really have a student, if he is not still wondering at the cosmos? The Latin studium (from which student is derived) means eagerness, zeal, enthusiasm, even fondness and affection. We could argue that without zeal and affection for truth, goodness and beauty, without love for the lovely–a student cannot truly be a student.

For what it is worth, I explore this theme in the following webinar, recorded and available here: Education in Wonder and Curiosity Webinar

by Christopher Perrin, PhD | Aug 12, 2013 | Articles

Well, most of us are now preparing to resume school in the next few weeks. Some of you have already started. Some of you never stopped. In fact, while formal schooling may have a yearly rhythm with starting and ending dates, learning itself transcends such boundaries. In fact, while formal schooling is an important part of learning, it is only a part. The late Jacques Barzun said that schools can teach but not educate, because the larger enterprise of education (the long, ongoing process of cultivating and civilizing a human soul) only occurs in the context of the larger community of parents, work, friends, church… and school. So learning should not be something we relegate only to school–it is occurring all the time, either poorly or well and by a dozen different “teachers.”

As we “go back to school” we might remember this, so that we don’t expect too much from formal schooling, and so that we continue to expect more from other sources of communal education. Parents are still the most important teachers that students have. One could argue that the student himself is his own most important teacher, for until he decides to learn for himself he not really even a student (the original meaning of student contain the idea of one who is zealous and eager for knowledge, from the Latin studere: to be eager, earnest, zealous). Are your students returning to school as zealots for truth, goodness and beauty? Then they are ready for school, which is to say they have been students all summer long.

by Christopher Perrin, PhD | Jun 12, 2013 | Articles, Uncategorized

I just posted an article about C. S. Lewis’s book The Abolition of Man—which you can see on this blog. Then I watched the video interview of Edward Snowden, the whistle blower of the controversial Prism surveillance program run by the NSA.

I won’t summarize all of the arguments of Lewis’s book, but he does set forward the thesis that new technologies that enable “man’s power over nature” turn out to be not to be the power of “man” generally, but rather the power of a few men over many other men.

The technologies that Lewis had in mind in 1947 were such things as the airplane, the wireless (radio) and contraceptives. Today, no doubt he would mention computers, smart phones…and the internet. These technologies do in fact bequeath power—power that most of us enjoy, like the power of emailing a friend, or listening to The Brother’s Karamazov, or checking our bank account–all while riding a bus, train or taxi (and even on some airplanes).

The power of these technologies are increasing rapidly, and while they may bless the man on the street, they also bolster the man at the bureau. We trust that our governmental agencies like the FBI, CIA and NSA use these great powers well, for our welfare and safety. If we ever suspect that they are using these powers to control, contain and condition the man on the street…well we become a bit nervous and edgy. The same technology that enables the NSA to track a potential terrorist, enables it to track me… a potential dissident. But our government wants (even encourages?) dissidence, or political free speech even of those critical of government policy. Right?

Lewis notes that when a culture has jettisoned objective value (what he also calls the Tao)—real, knowable truth and goodness—then gradually the way it wields power shifts from serving people to conditioning them to act the way the power-holders think best. And what a power-holder thinks best is not determined by an objective standard of what is right and good, precisely because such standards have been rejected. How then to do the power-holders make their decisions? They do what they please—that is to say they follow whatever impulses come to them as the strongest. These power-holders themselves may become what Lewis calls “Conditioners” and “man-moulders:”

They are, rather, not men (in the old sense) at all. They are, if you like, men who have sacrificed their own share in traditional humanity in order to devote themselves to the task of deciding what ‘Humanity’ shall henceforth mean. ‘Good’ and ‘bad,’ applied to them, are words without content: for it is from them that the content of these words is henceforward to be derived.

Could it be that immense power in the hands of few, in a culture without objective value will lead to man-moulding policies that seek to shape citizens into conformity with the prevailing ideals of those exercising this power? Is controlling and conditioning citizens not a great temptation to those possessing power—but no traditional morality? Lewis thinks that these amoral men are not bad men, because they have ceased to be men at all:

It is not that they are bad men. They are not men at all. Stepping outside the Tao, they have stepped into the void. Nor are their subjects necessarily unhappy men. They are not men at all: they are artifacts. Man’s final conquest has proved to be the abolition of Man.

Yes, but can’t we take solace in knowing that these power-holders are going to treat us fairly and well (certainly not as artifacts)? Surely, the great majority of people in these agencies will act for our good, or at least the common good. Lewis, I think, would qualify his answer. To those who hold to objective value (the Tao), we may expect some reasonable degree of benevolent treatment. But what should we expect from those who have rejected objective value?

I am very doubtful whether history show us one example of a man, who, having stepped outside traditional morality and attained power, has used that power benevolently. I am inclined to think that the Conditioners will hate the conditioned.

In Orwell’s 1984, the protagonist Winston Smith (after a great deal of conditioning) learns to love Big Brother, with tears in his eyes. But Lewis suggests that Big Brother never loves the little brother, the man on the street. Neither does Orwell. The man-moulders want to control, shape and produce a new humanity, what Lewis calls a post-humanity.

This is a pessimistic note to be sure. Chesterton says somewhere that he may enjoy a lively dinner conversation with a houseguest who is a moral relativist; but he will still hide the silver at night. Can we trust the good people at the FBI, CIA and NSA? Are they good people? Are they even people?

Finally, do we regard even Edward Snowden as good? If so, by what standard? Watch as most commentators call him either good or bad, but without appealing to any clear standard of objective truth or goodness. The testimony of Snowden himself doubles the irony, as even he does not appeal to any clear standards either. His view of the human good life seems to be the common “live and let live” as every man sees fit. Freedom to many American is now freedom to do as we please and create our own “morality.” Why can’t the folks at the NSA do the same? We all live by…impulse.

I have no way of proving this thesis, but I think that roughly half of all American have rejected objective value, and we are the midst of living out the consequences of this rejection in a thousand ways. Could it be that half of the people working in the FBI, CIA and NSA are themselves without a polished moral compass? We may call for investigations and committee hearings and protest loudly, but until we return to the Tao, we will have no basis to criticize or demand reform. Instead we will pit the impulses of the man on the street against the impulses of the man with the power, with no doubt as to who will win.

by Christopher Perrin, PhD | Jun 12, 2013 | Articles, Book Reviews

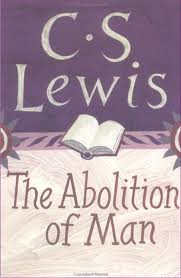

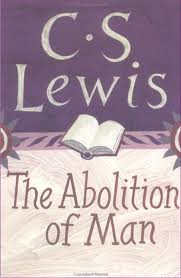

The Abolition of Man–A Review for Classical Educators

C. S. Lewis

The Abolition of Man was first published in 1947, just two years after the end of the second World War, after a great deal of abolition indeed. Lewis’ book, however, is not about man’s abolition by bombing and battles, but by grammar books and teaching methods. Eventually he does address propaganda (think Nazi propaganda) and conditioning as the eventual teaching method employed by a controlling state.

The Abolition of Man is one of C. S. Lewis’ smaller books. It is not, however, a small read. In this little book, Lewis seeks to swim upstream into a very brisk current, and one feels the pressure of that fight and the strong push against Lewis’s thought that exists everywhere today, as it did a generation ago when he wrote it.

When I read The Abolition of Man—and I have read it some five times—I find myself in the water with Lewis, kicking for all I am worth. Then occasionally I feel myself sliding downstream, for modern thought about education and “values” has a pull on me at times. The essence of his book is straightforward: there is a real, knowable world with objects that merit our blame and praise. At one place Lewis calls this the doctrine of objective value, though he also uses “The Tao” for shorthand.

How can that seemingly self-evident truth make for such a hard, brief book? Well for one this doctrine is attacked indirectly at every side so that we have been conditioned to resist it; secondly the denial of this doctrine leads to several ideas and practices that at first, don’t seem related, but in fact are. Finally this book is a hard read because we need its wisdom so much, but have employed it so little. Lewis makes a compelling case for cultivating the affections of our students, but we have largely taught our students the way were taught—too often encouraging our students to invent their own moral universe.

Lewis makes an argument for objective value, not by quoting biblical texts, church fathers or theologians, though he could. He does not quote philosophers of aesthetics, though he could. He appeals rather to the universal consensus of the major world religions and moral or ethical philosophy. Though he is a Christian, he makes an appeal merely as a theist, pointing out that theists of all kinds recognize and confess that their exist objects in the world (like mountains, trees, sunsets, waterfalls) and real human qualities (like courage, generosity and self-sacrificing love) that merit our praise and accompanying emotions of gratitude, admiration and love. As well, the universal tradition recognizes and confesses that there are some objects in the world (like deformity and destroyed landscapes) and some human qualities (like thievery, lying and cowardice) the merit our blame and accompanying emotions of revulsion, anger and sorrow.

If you assent to this doctrine of objective value, you may hold to it on rational grounds as you think about it just now. But isn’t beauty in the eye of the beholder? Do you confess (at times) “to each his own” and “live and let live”? Are not your reactions to many objects and qualities actually—your reactions? They may not be my reactions, for I am a different person than you with a different background, different training, different assumptions and preferences. We both see the storm approach and lightening strike. “The glory of God and his power!” you may say. “No soccer game today!” I may say. Are not “value judgments” largely (or at least significantly) subjective? If you feel the force of this suggestion, then you are in common company, first because we have all been conditioned to think that all value judgments are subjective and second because there is some truth to the suggestion (we all bring personal biography to our assessments in varying degrees). The truth in it, combined with our incessant conditioning (which distorts the truth in it) makes reading Lewis’ book a challenge for many of us.

For a classical educator, things can get more complicated yet, when we read that classical tradition from Plato onward tells us that we must cultivate the affections and sensibilities of the young to love that which is lovely even before their age of reason. This is truly alien to our culture: we must train the emotions of children to love the good and beautiful and hate the bad and ugly. What? Isn’t this indoctrination? Isn’t this imposing our view of what is true, good and beautiful on someone else—and a vulnerable, impressionable child at that? Don’t we need rather to encourage the young child to seek out her own preferred good and bad things, find her own style of beautiful and even her own truths? How dare we stunt or destroy this child’s freedom to choose her values and become what she wishes!

Well Lewis, Plato, Aristotle and Augustine all say that we should do precisely that. The true, good and beautiful are real and knowable and should not only be presented to children, but they should be encouraged to love the true, good and beautiful. Their emotions should be cultivated so that they blame and hate the false, bad and ugly as well. Are you kicking upstream? Slipping a little?

Now note the related implications. If you accept the doctrine of objective value and you are a teacher, should you not regularly show forth what you regard as universally true, good and beautiful objects and acts? Should you not seek to “order the loves” of your students and exhort them to flee disordered loves for those things that are not true, good and beautiful? Is there anything beautiful in your classroom—or your manner of speech? Are you full of admiration and praise, and then in proper measure full of blame and critique? Or is everything you teach left in a mush for students to sort out and think as they wish?

Because we have been conditioned to resist calling something truly lovely and then loving it, we often lack the courage to praise, extol, admire and praise. We also lack the courage to blame the ugly, despise the lie, flee the immoral. We have become humans without robust emotion, without conviction, without affections, without heart. In Lewis’s words, we have become men without chests.

But the implications of the doctrine of objective values travel in another direction too. If one rejects this doctrine, what happens to education? How will we teach? Well wittingly or not, certain things follow, or eventually follow. If all value judgments are merely subjective, then we merely describe our feelings when we make such judgments—which amounts to nothing particularly profound. Thus when our student Susan says, “That horse is beautiful” she merely states that she has certain pleasant feelings when she looks at the horse, but says nothing objectively real about the horse. What this does to teaching we have all seen and experienced. Teaching to a large extent becomes a group exploration of our individual reactions, responses and feelings, often celebrated as our individual, autonomous freedom. Instead of celebrating something as universally lovely, we celebrate the individual, free student and his opinions; each child is a unique snowflake (just like every other student). What we don’t realize is how profoundly this view has affected us. Do you feel the current? Don’t we all want to tell our children they indeed are unique and wonderful? Aren’t virtually all their ideas to be admired and encouraged? Don’t you want to view your own ideas, inclinations and opinions in a similar way? We have been carried down this river for many years.

If a teacher does not believe in object value, it does not mean that he won’t teach values. Lewis argues that the teacher who denies such values will in fact teach a very clear set of values—and they will be the prevailing values of “his set” the assumed values of the modern establishment of which he is a part. Even the denial of objective value is itself a value after all—a confessed common good. Lewis’ point is that all humans will hold to universal values—even those denying them. Such values will be hidden and assumed by such teachers, however.

Lewis concludes his book, by pointing to an ominous implication of rejecting the doctrine of objective value. If there is no objective value, then our educators will eventually become our conditioners, conditioning us to states of mind convenient to the aims of those in power. It will employ pervasive propaganda and various forms of coercion. There is simply no other means of appeal to persuade people to a course of belief, action or behavior. If there is no objective value, and we are unique and free to feel as we wish, how will we ever act in concert toward the same ends? A million autonomous snowflakes will not drift into a civilization. If there is to be a cohesive society (without objective value) then it must be conditioned and forced. A state-sponsored indoctrination follows in which humans are manipulated into serving the state’s interest even if this means the abolition of the chest and heart of man, or the abolition of man himself.

The subtitle of Lewis’ book is “How Education Shapes Man’s Sense of Morality.” We educators are indeed shaping the souls of humans beings, shaping them to love one thing or another. As we read, and re-read this profound little book, we should pay attention to the way in which our own poor education has shaped our sense of morality—our sense of what is true, good and beautiful. And since we are swimming against the current, we should do so together and kick, kick, kick.

Questions for educators:

- Are you reluctant to praise the true, good and beautiful before your students?

- What “hidden” values do you assume that come through indirectly in your teaching?

- What are the hidden values in your school culture and community?

- In what ways does the subjectivist view of morality linger in your teaching or school community?